Exemption for under 25yrs, GhC30 for first timers….

By Prince Ahenkorah

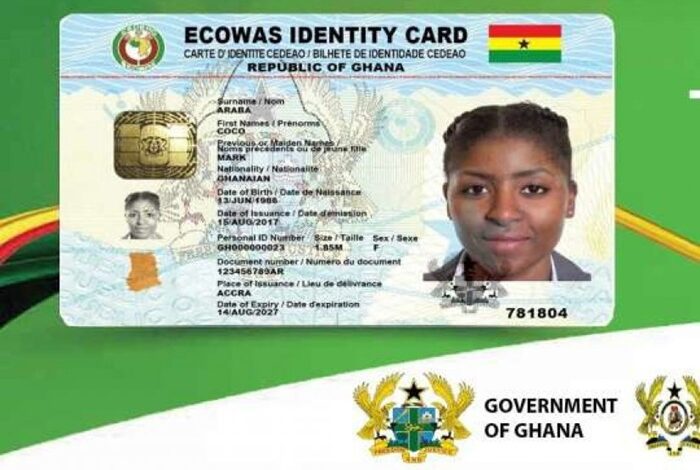

The National Identification Authority (NIA) has announced a significant overhaul of fees for Ghana Card services, a move critics warn could deepen financial exclusion and create a two-tiered system of citizenship in the digital age. The new charges, effective February 2, introduce a landmark fee for first-time adult registrations, marking a pivotal shift from the previously universal free enrolment.

Under the revised structure, Ghanaians aged 25 and above will now pay GH¢30 for their first card, while those under 25 remain exempt. More steeply, the cost of replacing a lost or damaged card soars to GH¢200, with renewal set at GH¢150.

For foreign nationals, fees are pegged to the US dollar, at $120 for registration and $78 for annual renewal.

The NIA, in a statement, justified the increases as a necessity driven by “rising operational expenses,” including technology licensing, cybersecurity, and logistics. The Authority framed the hike the first since 2023 as essential for the “long-term sustainability” of the national identification system, following parliamentary approval of amendments to the Fees and Charges Regulations.

While positioned as a routine adjustment under the Fees and Charges (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act, the policy shift is philosophically profound. It transitions the Ghana Card from a freely provided public good, foundational to civic identity, to a cost-recovery service.

This raises immediate questions about affordability for the poor, the elderly in rural communities, and informal sector workers for whom GH¢200 represents a substantial financial shock.

The announcement coincides with NIA’s stated “intensifying efforts to curb illegal registration activities.” The simultaneous timing is unlikely to be coincidental.

By formalising and raising fees, the Authority aims to dismantle the grey market of unauthorized agents who have capitalized on system inefficiencies and high demand. The public warning to “avoid unauthorized middlemen” is an explicit acknowledgment of this corrosive parallel system.

However, analysts suggest the high replacement fee may inadvertently fuel the very illicit market it seeks to suppress. “When the state-imposed cost of a mandatory document reaches GH¢200, you create a massive incentive for forgery and black-market solutions,” notes governance researcher Dr. Akua Mensah. “The state must ensure its own services are accessible and affordable, or it cedes ground to criminals.”

The Ghana Card is the linchpin of the government’s digitalization agenda, required for everything from bank accounts and SIM registration to accessing public services and social programmes.

This move effectively places a monetary gate on entry to the formal digital economy. Proponents argue that a sustainable system requires user contributions. Opponents counter that marginalizing the poor from the official identity system undermines the very goals of inclusion and efficient governance the card is meant to advance.

The exemption for youth under 25 is a politically sensitive carve-out, likely intended to soften backlash and frame the card as an investment in the next generation. Yet, it creates an arbitrary cliff-edge at the 25th birthday, transforming a right of citizenship into a paid-for adulthood.

The fee revision is more than a budgetary adjustment; it is a test of the government’s commitment to equitable digitalization. As the NIA seeks to protect the “integrity of the national identity database,” the greater risk may be compromising its comprehensiveness. The coming months will reveal whether these new charges will secure the system’s financial sustainability or price a significant portion of the population out of legal identity, with profound consequences for their economic and social rights. The Ghana Card was meant to unify the nation under one digital umbrella; these new fees risk tearing a hole in its cover.