In a significant overture to the judiciary, Finance Minister Dr. Cassiel Ato Forson has revealed he is actively considering a policy shift to allow the Judicial Service to retain 100% of its Internally Generated Funds (IGF) to meet urgent operational needs.

The proposal, aimed at easing acute financial constraints, follows a high-stakes visit by Chief Justice Paul Baffoe-Bonnie to the Finance Ministry on 21 January a meeting that came days after the judiciary threatened an indefinite strike over unpaid salary arrears.

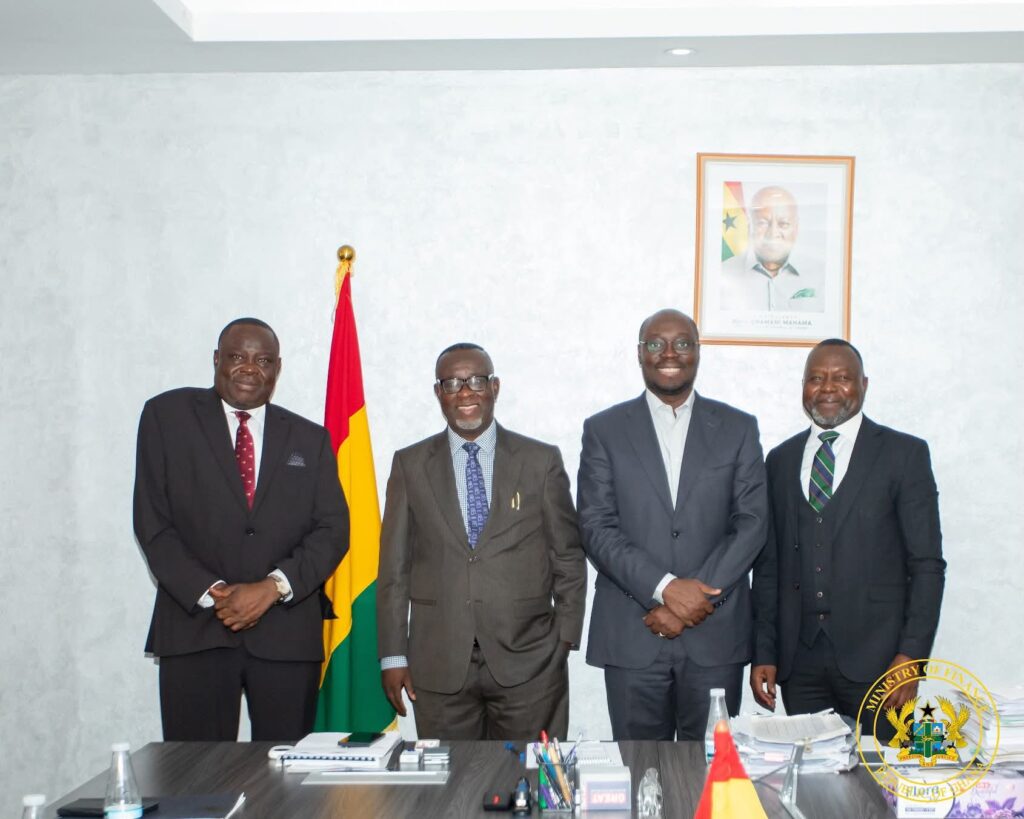

The Chief Justice led a heavyweight delegation, including Supreme Court judge Justice Gabriel Pwamang, the Acting Director of the Ghana School of Law Prof. Raymond Atuguba, and Judicial Secretary Musah Ahmed. Also present was Attorney-General Dr. Dominic Ayine, signalling the meeting’s cross-governmental importance.

The closed-door talks occurred against a backdrop of severe institutional strain. The Judicial Service had scheduled an indefinite industrial action to commence on 19 January, demanding the payment of salary arrears linked to a 2025 base pay increase announced by President John Mahama.

The strike, which would have paralysed the courts nationwide, was only suspended following intervention by the National Labour Commission (NLC).

Minister Forson’s social media summary of the meeting acknowledged the “difficult environment” under which the judiciary operates and pledged closer collaboration. The offer to explore full retention of IGF revenue from court fees, fines, and other services is a direct, pragmatic response to the judiciary’s chronic underfunding, which has long been a source of tension with the executive.

Chief Justice Baffoe-Bonnie’s presentation outlined two critical crises: severe congestion undermining justice delivery and deteriorating working conditions for judicial staff.

The request for support is not merely for operational budgets but for “sustained institutional support to improve efficiency and outcomes.” This framing elevates the issue from a financial dispute to a fundamental matter of governance and constitutional functionality.

The proposed 100% IGF retention represents a potential landmark change in fiscal governance. Currently, most IGF collected by state agencies is surrendered to the Consolidated Fund, with allocations subject to parliamentary approval.

Allowing the judiciary full control would grant it unprecedented budgetary autonomy, potentially improving responsiveness but also raising questions about parliamentary oversight and equity among other underfunded state institutions.

For the Mahama administration, the move is a strategic necessity. A judiciary on strike would be a political catastrophe, crippling government business and undermining the rule of law.

Solving the funding crisis through IGF retention offers a solution that does not immediately pressure the strained national budget. However, it requires navigating complex Public Financial Management (PFM) regulations.

For the judiciary, it is a test of managerial capacity. Full control of IGF brings the responsibility to manage these resources efficiently and transparently, without the traditional recourse to blaming the Finance Ministry for shortfalls.

The meeting and Forson’s proposal have temporarily calmed tensions, but the underlying issues remain. It is unclear if the unresolved salary arrears—the original trigger for the strike threat were settled.

The move signals the government’s preference for sector-specific, off-budget solutions to fiscal crises. If implemented, it could set a precedent for other aggrieved public services, potentially fragmenting national fiscal control.

The coming weeks will reveal whether this is a genuine pivot towards judicial financial autonomy or a tactical manoeuvre to avert an immediate disaster, with long-term reforms still pending.