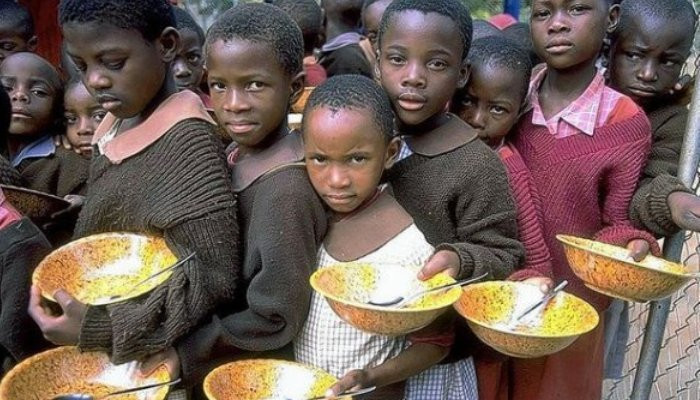

Ghana’s food insecurity situation has worsened significantly, raising serious concerns about its implications for economic stability and long-term development.

According to the latest Quarterly Food Insecurity Report released by the Ghana Statistical Service, national food insecurity prevalence rose from 35.3 percent in the first quarter of 2024 to 38.1 percent by the third quarter of 2025. This increase reflects a volatile upward trend, with food insecurity peaking at 41.1 percent in the second quarter of 2025 before easing slightly.

In population terms, the figures are stark. The number of food-insecure persons increased from 11.2 million in early 2024 to a peak of 13.4 million people by the second quarter of 2025. Although there was a marginal decline in the most recent quarter, more than 13 million Ghanaians remain exposed to hunger risks, underscoring the scale and persistence of the challenge.

Food Insecurity Beyond a Social Issue

Speaking after the release of the report, Government Statistician Dr. Alhassan Iddrisu stressed that food insecurity should not be viewed purely as a welfare concern. He warned that its effects ripple across the broader economy and threaten national development.

“Food insecurity is not just a social issue. It affects household welfare, child health, global productivity, business confidence and ultimately national development,” he said.

This perspective reframes hunger as a macroeconomic risk — Poor nutrition weakens labour productivity, increases health care costs and undermines learning outcomes among children. Over time, these effects constrain economic growth and reduce the resilience of households and businesses alike.

How the Data Was Measured

The report is anchored on the Food Insecurity Experience Scale, an internationally comparable measurement tool aligned with Sustainable Development Goal Two, which seeks to end hunger and promote sustainable food systems.

The methodology relies on eight experience-based questions that capture household food-related experiences over a three-month period. These range from anxiety about food availability to extreme deprivation such as skipping meals or going an entire day without food.

Using the Rasch statistical model, households are classified as food secure, moderately food insecure or severely food insecure. The data is drawn from the Quarterly Labour Force Survey, enabling food insecurity to be monitored every three months rather than annually. This approach allows policymakers to respond more quickly to emerging risks and shocks.

Education and Gender Drive Sharp Inequalities

Beyond national averages, the report highlights deep disparities across social and demographic groups. Food insecurity declined consistently with higher levels of education. Households headed by individuals with no formal education recorded the highest prevalence, averaging about 50 percent, compared to just 15 percent among households headed by persons with tertiary education.

Gender also played a critical role. Female-headed households, particularly in rural areas, were more exposed to moderate and severe food insecurity. These households often face limited access to productive resources, credit and stable income opportunities, making them more vulnerable to economic and seasonal shocks.

Household Composition and Health Risks

Household structure further shaped food security outcomes. Households with both children and elderly members recorded significantly higher food insecurity, averaging 44 percent in 2025. Poor child health outcomes were closely linked to elevated food insecurity levels, reinforcing the cycle between hunger and long-term human capital losses.

In rural areas, the situation was particularly severe. Female-headed households with underweight members recorded food insecurity rates exceeding 80 percent in the third quarter of 2025. These figures point to pockets of extreme vulnerability that require targeted interventions rather than broad, one-size-fits-all policies.

Regional Disparities Remain Pronounced

Geographical differences remained a defining feature of Ghana’s food insecurity landscape. The Upper West, North East, Savanna and Volta regions consistently recorded the highest food insecurity rates, reflecting structural challenges linked to poverty, climate exposure and limited economic diversification.

By contrast, Oti and Greater Accra recorded the lowest levels. Food insecurity in the Oti Region declined from 23.8 percent to 18.4 percent over the period under review. However, the Volta Region recorded the highest food insecurity rate among households with both children and elderly persons, reaching 52.3 percent in the third quarter of 2025.

Economic Shocks and Growing Risks

Analysis of individual indicators showed that worrying about food was the most common experience nationally, affecting an average of 53 percent of households. Severe deprivation, such as going an entire day without food, remained relatively low at 3.1 percent in the third quarter of 2025. Even so, rural households were more affected by eating less than they should compared to urban households, highlighting persistent rural-urban divides.

Dr. Iddrisu cautioned that food insecurity is highly sensitive to economic conditions, seasonal patterns and unexpected shocks. He noted that the overall upward trend since early 2024 signals growing vulnerability, particularly as Ghana navigates fiscal consolidation, climate risks and global economic uncertainty.

The report concludes that while short-term improvements are possible, reversing the trend will require sustained and coordinated policy responses. These include strengthening agricultural productivity, improving social protection targeting, supporting vulnerable households and ensuring that food systems remain resilient to shocks.

As Ghana pursues its development agenda and commitments under the Sustainable Development Goals, the findings serve as a warning. Without decisive action, rising hunger risks could undermine household welfare, weaken productivity and threaten the country’s economic future.