By Gifty Boateng

The children of Asiukrow in the Upper West Akim Municipality are still balancing on peril. More than a year after President John Dramani Mahama personally intervened to order the construction of a footbridge over the stream that separates them from their school, the crossing remains as deadly as ever.

One child has already paid the ultimate price. According to residents, a pupil attempting to cross alone two months after the presidential directive drowned a death that might have been prevented had the promised bridge materialised.

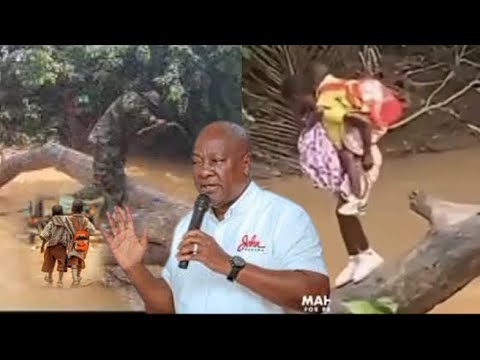

The President’s attention was first drawn to the community’s plight in February 2025, barely a month into his administration, through a heartbreaking social media post showing children inching across a fallen tree trunk, their tiny frames carrying each other over the water. The images moved Mahama to action.

“Earlier today, the MP for Lower West Akim visited the Asiukrow community and assured them the Eastern Regional Minister will also visit, as we work to permanently and urgently resolve the challenge,” the President stated at the time. He ordered engineers from the 48 Engineer Regiment of the Ghana Armed Forces to deploy immediately.

What followed was a procession of officialdom. The then-Defence Minister, the late Dr Edward Kofi Omane Boamah, dispatched a representative to assess the situation.

The Eastern Regional Minister, Rita Akosua Awatey, toured the site. The MP, Emmanuel Drah, was present. Officers from the 48 Engineers surveyed the terrain. Officials from Feeder Roads added their technical input.

The community waited. The broken tree that had served as a makeshift bridge hazardous but at least functional was removed by local authorities led by the Assembly Member, who assured residents it was being cleared to make way for construction. The promise was that the bridge was imminent.

Today, the stream flows uninterrupted. The children are back to improvising, their lives hanging on balance and luck. The MP for Upper West Akim, Emmanuel Drah, is now publicly pleading for intervention from Roads and Highways Minister Governs Kwame Agbodza and the President himself, describing the situation as an “emergency.”

But the machinery of government grinds slow. Drah admits that despite the high-level visits and presidential urgency, the process has been strangled by bureaucracy. Whenever he follows up, he is told the file awaits “commitment authorisation” from the Finance Minister a technical hold that, in plain language, means no funds have been released.

The MP’s desperation is palpable. He confides that he now avoids the community altogether, unable to face constituents whose hopes were raised and then abandoned. The last time party executives attempted a visit, residents chased them away.

Drah is now racing against nature. “This is the right time for authorities to act, at this time that the water level is down,” he pleads. The dry season offers a narrow window for construction before the rains return and the stream swells again.

But the window is closing, and the machinery shows no sign of movement.

President Mahama’s words from February 2025 now carry a bitter echo: “Our quest to Reset Ghana includes a determination to remove barriers to education and healthcare across the country.”

At Asiukrow, the barrier remains firmly in place. One child is dead. Scores more continue to risk the same fate for the right to learn.

The contrast between presidential intent and bureaucratic execution could not be starker.

At the highest level, the directive was clear, the urgency acknowledged, the military engineers identified. But somewhere between corridors of power and the stream at Asiukrow, the order was lost in the machinery.

For the children crossing the water each morning, the promises of officials mean nothing. The only thing that matters is whether they make it to the other side.