Over Who Wins and Loses ‘Floor’ Price Raise as Public Hails Mahama

By Gifty Boateng

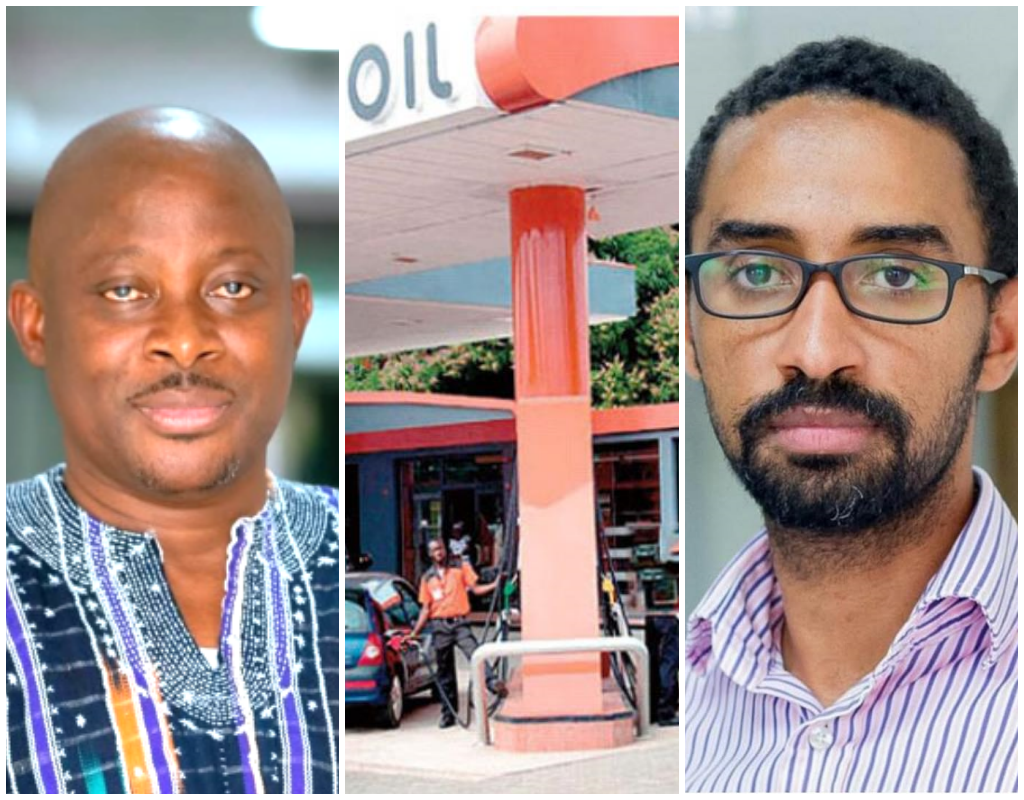

A bitter public feud has erupted between the chief executives of Ghana’s two largest fuel retailers, laying bare a simmering conflict over government price controls that pits free-market rhetoric against accusations of hypocrisy, with consumers caught in the middle.

The war of words began when Philip Kwame Tieku, CEO of the privately-owned StarOil, suggested on social media that his company could slash petrol prices to GH₵9.50 per litre during late-night hours to support the “night time economy.” He argued this was only prevented by a government-imposed price floor a minimum price set every two weeks by the National Petroleum Authority (NPA) which currently stands at GH₵9.80 per litre.

“Imagine StarOil pricing petrol at 9.50 per litre after 10pm each night till 4AM…but that will be below NPA floor price,” Tieku wrote.

Within days, his claim was met with a sharp rebuke from Edward Abambire Bawa, Group Managing Director of the state-owned GOIL PLC. In a detailed Facebook post, Bawa did not name Tieku but directly challenged the credibility of any oil marketing company (OMC) calling for deeper price cuts. His core accusation: these very companies are not even selling at the current, lower floor price.

“Some industry players are claiming that they can reduce prices further, yet in reality they cannot even compete at the approved floor price of GH₵9.80 for PMS in this pricing window,” Bawa wrote. He pointed out that the OMCs making these claims are instead selling at GH₵9.97 per litre. “Calling for deeper price reductions while pricing above the regulated floor undermines the credibility of that claim.”

Tieku fired back by invoking corporate history and customer loyalty. He recalled the 2022 fuel price crisis, claiming StarOil used its network to “cushion consumers” while an “inefficient” competitor a clear jab at state-owned GOIL priced alongside foreign firms. “Now they come questioning our credibility in low pricing?” he asked, revealing that StarOil had just recorded its highest-ever daily sales.

At stake is more than a corporate rivalry; it’s a fundamental debate about competition, regulation, and transparency in a market where fuel prices are a daily economic trauma for millions of Ghanaians.

The NPA’s bi-weekly price floor, established under the Petroleum Products Pricing Guidelines, 2024, is designed to prevent what regulators fear could be a destructive “price war” that could drive smaller players out of business and lead to market instability.

But critics, including the influential Chamber of Petroleum Consumers (COPEC), see it as a cap in disguise that stifles competition and keeps prices artificially high. COPEC’s Executive Secretary, Duncan Amoah, has called for the floor’s immediate abolition, labeling it “anti-consumer.”

“Any OMC that is willing and capable of selling fuel at a lower price is prevented from doing so,” Amoah told The New Republic. “The current arrangement stifles competition… It denies consumers the benefits of competitive pricing.”

The policy creates a paradoxical marketplace. While prices are officially “deregulated” and OMCs are free to set their own rates, they cannot go below the state’s minimum. This has led to a market where prices cluster tightly at or just above the floor, with dramatic claims about potential savings that are impossible to verify under the current rules.

The CEOs’ clash reveals the strategic calculations beneath the surface. For a growing private giant like StarOil which overtook GOIL in sales volume in 2025 agitating for the removal of the floor is a potential market-share play.

It could use its scale to undercut competitors, especially smaller OMCs. For GOIL, the state-owned incumbent with a national service mandate, the floor provides stability and protects against a race to the bottom that could threaten its network and the government’s significant investment.

The NPA did not respond to requests for comment on the specific allegations raised by the two CEOs or on the future of the pricing policy.

For consumers, the social media spat is a frustrating spectacle. It highlights a market where prices are a subject of corporate and regulatory negotiation, often feeling disconnected from the international crude oil prices and exchange rates cited by companies.

The promise of cheaper fuel at night remains theoretical, locked behind a regulatory barrier whose ultimate purpose protecting competition or protecting competitors is now the central question of a very public fight.

As the two most powerful figures in Ghana’s fuel retail sector trade accusations, the underlying data remains opaque.

The public cannot easily audit which companies are selling at what margin, or what the true “competitive” price might be. The debate, played out on Facebook, is ultimately a fight over who gets to define fairness: the state setting a minimum, or the market discovering a price, with consumers left to hope the winner brings tangible relief to the pump.