As NDC Government Break Economic Barriers

By Leo Nelson

Ghana is on course to cement its status as a regional heavyweight, with the International Monetary Fund and multilateral lenders projecting its Gross Domestic Product will hit $113.49 billion in 2026. The figure, a rise from an estimated $108.1 billion in 2025, is expected to rank the country as the eighth largest economy in Africa.

The headline numbers tell a story of cautious optimism. The projected 4.8% growth rate suggests an economy steadily finding its feet after the turbulence of recent years. Yet, beneath the surface, the trajectory reveals as much about the struggles of peers as it does about Ghana’s own recovery.

According to the data, Ghana will sit comfortably ahead of regional rivals like Côte d’Ivoire and Angola, but remains dwarfed by the continent’s traditional giants. South Africa leads the pack with a projected $443.64 billion, followed by Egypt ($399.51 billion) and a resurgent Nigeria ($334.34 billion). Algeria, Morocco, Kenya, and Ethiopia also outrank Accra, underscoring the gap that still separates the West African state from the continent’s top tier.

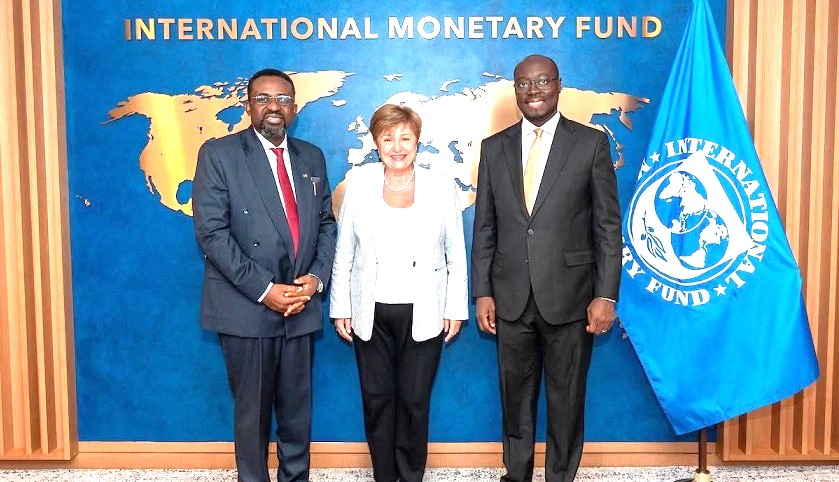

For the Mahama administration, the ranking is a vindication of its push for fiscal discipline. After years of navigating sovereign debt restructuring, IMF programmes, and volatile currency markets, the government is keen to project an image of stability. The projection, officials argue, reflects renewed investor confidence and the payoff of painful but necessary reforms.

What sets Ghana apart from many of its neighbours, however, is not just the size of its economy but its structure. Unlike oil-dependent Angola or cocoa-reliant Côte d’Ivoire, Accra has spent the last decade building a more diversified base.

Gold remains the bedrock of foreign exchange earnings, while cocoa continues to provide a steady, if politically sensitive, stream of revenue. But it is the oil and gas sector—bolstered by offshore production—that has increasingly underwritten the government’s fiscal ambitions. When global commodity prices wobble, the combination of resources offers a cushion few others enjoy.

Meanwhile, the services sector has quietly become the engine of growth. Telecommunications, financial services, and a burgeoning tech scene are absorbing labour and driving consumption. This is not your father’s Ghanaian economy; it is one where mobile money transfers often matter more than cocoa pod harvests.

The growth narrative is also being written in concrete and steel. Port expansions in Tema and Takoradi have streamlined trade logistics, while road corridors linking production zones to markets are gradually cutting costs for businesses. Energy sector investments, though still dogged by legacy debt, have at least reduced the risk of the debilitating power cuts dumsor’ that once crippled industry.

These projects are part of a broader strategy to make Ghana not just a stable economy, but a competitive one. For international investors scanning West Africa, Accra offers a combination of political stability, English-speaking bureaucracy, and improving infrastructure that few rivals can match.

Yet, the 4.8% growth projection, while welcome, is hardly a boom. It reflects a recovery, not a renaissance. Debt servicing still consumes a significant chunk of revenue, and the cedi’s vulnerability to external shocks remains a perennial headache. The government’s ability to sustain this trajectory will depend on whether it can move beyond stabilisation and into genuine industrial expansion.

The challenge now is to translate macroeconomic figures into tangible gains. Value addition whether in gold refining, cocoa processing, or manufacturing remains the missing piece of the puzzle. Without it, Ghana risks remaining an exporter of raw potential rather than a creator of finished wealth.

For now, the $113 billion projection offers the Mahama administration a useful talking point. In a region where economic mismanagement is the norm, Ghana’s steady, if unspectacular, climb up the continental rankings is a story of relative success. But as any Africa Confidential reader knows, league tables can be fleeting. The real test will be whether Accra can convert this numerical milestone into durable, inclusive growth.